By Stephanie Pappas | LiveScience

Earth’s hot, gooey center and its cold, hard outer shell are both responsible for the creeping (and sometimes catastrophic) movement of tectonic plates. But now new research reveals an intriguing balance of power — the oozing mantle creates supercontinents while the crust tears them apart.

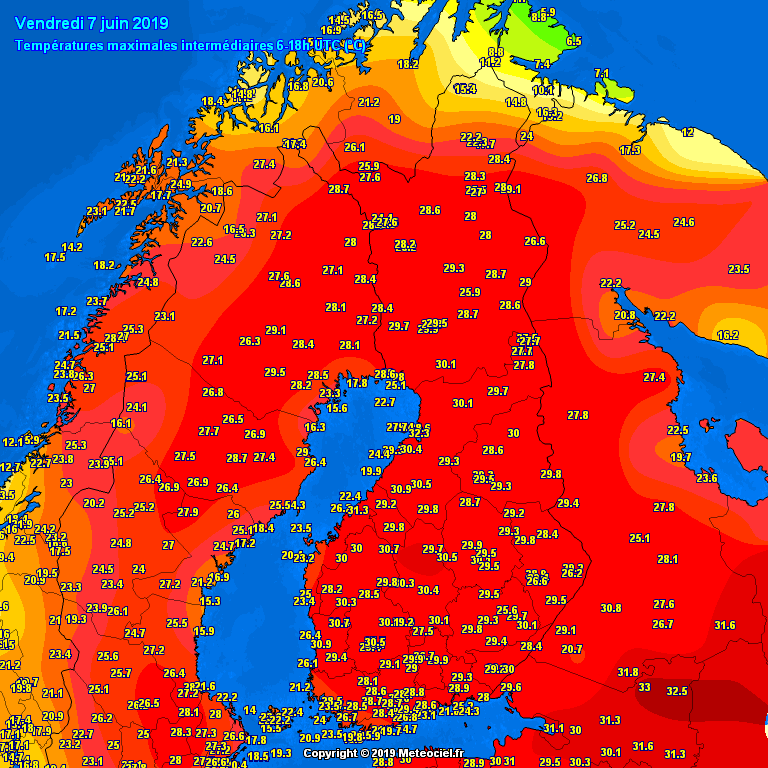

To come to this conclusion about the process of plate tectonics, the scientists created a new computer model of Earth with the crust and mantle considered as one seamless system. Over time, about 60% of tectonic movement at the surface of this virtual planet was driven by fairly shallow forces — within the first 62 miles (100 kilometers) of the surface. The deep, churning convection of the mantle drove the rest. The mantle became particularly important when the continents got pushed together to form supercontinents, while the shallow forces dominated when supercontinents broke apart in the model.

This “virtual Earth” is the first computer model that “views” the crust and mantle as an interconnected, dynamic system, the researchers reported Oct. 30 in the journal Science Advances. Previously, researchers would make models of heat-driven convection in the mantle that matched observations of the real mantle pretty well, but didn’t mimic the crust. And models of the plate tectonics in the crust could predict real-world observations of how these plates move, but didn’t mesh well with observations of the mantle. Clearly, something was missing in the way that models put the two systems together.

Crust plus mantle

Every grade-school model of Earth’s interior shows a thin layer of crust riding atop the hot, deformable layer of the mantle. This simplified model might give the impression that the crust is simply surfing the mantle, being moved this way and that by the inexplicable currents below.

But that isn’t quite right. Earth scientists have long known that the crust and mantle are part of the same system; they’re inescapably linked. That understanding has raised the question of whether forces at the surface — such as the subduction of one chunk of crust under another — or forces deep in the mantle are primarily driving the movement of the plates that make up the crust. The answer, Coltice and his colleagues found, is that the question is ill-posed. That’s because the two layers are so intertwined, they both make a contribution.

Over the past two decades, Coltice told Live Science, researchers have been working toward computer models that could represent the crust-mantle interactions realistically. In the early 2000s, some scientists developed models of heat-driven movement (convection) in the mantle that naturally gave rise to something that looked like plate tectonics on the surface. But those models were labor-intensive and didn’t get a lot of follow-up work, Coltice said.

Coltice and his colleagues worked for eight years on their new version of the models. Just running the simulation alone took 9 months.

Building a model Earth

Coltice and his team had to first create a virtual Earth, complete with realistic parameters: everything from heat flow to the size of tectonic plates to the length of time it typically takes for supercontinents to form and come apart.

There are many ways in which the model isn’t a perfect mimic of Earth, Coltice said. For example, the program doesn’t keep track of previous rock deformation, so rocks that have deformed before aren’t prone to deform more easily in the future in their model, as might be the case in real life. But the model still produced a realistic-looking virtual planet, complete with subduction zones, continental drift and oceanic ridges and trenches.

Beyond showing that mantle forces dominate when continents come together, the researchers found that hot columns of magma called mantle plumes are not the main reason that continents break apart. Subduction zones, where one chunk of crust is forced under another, are the drivers of continental break-up, Coltice said. Mantle plumes come into play later. Pre-existing rising plumes may reach surface rocks that have been weakened by the forces created at subduction zones. They then insinuate themselves into these weaker spots, making it more likely for the supercontinent to rift at that location.

The next step, Coltice said, is to bridge the model and the real world with observations. In the future, he said, the model could be used to explore everything from major volcanism events to how plate boundaries form to how the mantle moves around in relation to Earth’s rotation.